Spoilers Ahead.

This work of fiction was constantly filthy, to the point of occasionally inciting some feelings of contempt towards Houellebecq. At times it was insightful and relatable, but I found it largely nihilistic and cynical – views which I do not share, nor relate to. However, I did not finish this novel wishing I did not read it.

I can agree that at times, Houellebecq manages to use hedonism effectively as a mode of storytelling. Since he uses terms and subjects that are rarely discussed in literature, it provides sufficient ‘shock’ value. He uses this style very casually with Michel Djerzinski and Bruno, and through them, there are some rare moments of understanding.

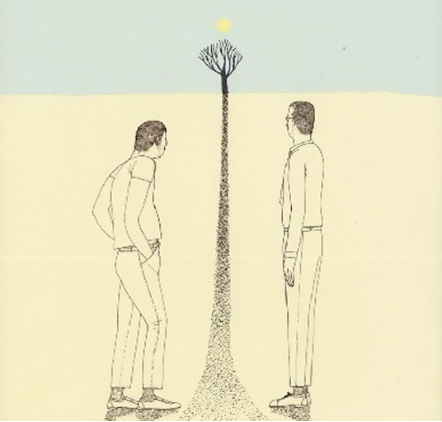

Sex is consistently at the forefront of these characters minds, and therefore to that of the reader as well. In this sense, when I reflect on the book, the issues of contemporary society that Houellebecq is working to dismantle take a backseat, and I feel as though the novel was just about the sex lives of brothers, Michel and Bruno. Only with active reflection, am I able to pinpoint the underlying societal messages that Houellebecq is attacking, mainly through the stark contrast between Michel and Bruno’s lives. However, I still struggle to accept that this novel must be so twisted in order to portray these messages effectively.

An area in which I feel that Houellebecq succeeds in this book, is through his criticism of an ‘atomised’ society – where religion has fallen to a shallow new age. The meaningless sexual connections that Bruno desperately seeks at the start of the novel give way to warm, fulfilling—though flawed—relationships. The same is true for Michel. The filthy language used throughout this change helps to amplify the contrast between depraved lustful encounters to healthier and meaningful love. In this, the reader is forced to confront the complications of a society that promotes sexual freedom as progress and empowerment, while overlooking its effects on human psyche.

The way women (occasionally men too) are portrayed in Atomised is so vulgar that it makes it hard to tell whether this perspective reflects Houellebecq’s own views or serves a literary purpose. Women are often described in terms of their physical features and sex organs, reducing them to crude portrayals and inhuman characteristics. Through the male characters’ perspectives, the reader is drawn into a view that feels as shameful and pathetic as the mindset of someone who would think this way. This is just one of the ways men are degraded in this novel. The male main characters are portrayed as pathetic or dissolute, while women are described as useful, kind, and caring. This same contrast is seen for the old and young respectively. While this is powerful in its ability to push Houellebecq’s societal criticism, this book won’t make you feel excited about being a man, or about getting older. I guess that’s cynicism at its finest.

At times it felt as though this book might end happily despite its overall pessimism, but Houellebecq quickly dashes this hope with tragic and otherwise quite depressing deaths for the love interests of Michel and Bruno. While frustrating, this felt grimly appropriate for a book that finishes with Michael Djerzinski’s dystopian discovery at the end of the novel—the biological re-engineering of humanity to eliminate the need for love.

This book is 384 pages.

Leave a Reply